Midrange Weekly August 9

YOUR WEEKLY ROUND UP ON WHAT’S GOT THE MIDRANGE STAFF’S ATTENTION

Midrange Staff @midrangeyvr

Hello friends and welcome back to Midrange Weekly. We wouldn’t be much of a Canadian publication if we didn’t talk about the weather this week and holy shit it actually rained in Vancouver. That’s… really all there is to say about that it would seem. (Ed note- get Tristan off the intros what the hell kind of opening was that?). We’ve got a bit of a longer than usual Weekly this time around with Jamie covering a couple topics and Tristan taking a deadline induced red bull binge a little too far. Oddly enough it’s Jamie writing about politics and Tristan taking about food this time so nothing really makes sense any more. Good luck to you all.

Some Thoughts On Pig

Honestly, Jamie should be writing about this one- he’s the food guy.

Unless that’s the point of Pig, to interrogate not so much the utility and efficacy of our colloquial foodie culture, but to examine its meaning. More urgently, to dismantle that meaning and search for a deeper understanding of what food can represent for us beyond sustenance and beyond the hierarchal frivolity of the cultural elitism that comes from the greater gestalt of the restaurant industry. It endeavours, with a near infiltrating air of grace and subtlety, to offer instead the ways in which memory, community, empathy, and fragility are inexorably entwined within the simple act of having a meal. These confluences are messy, draining, cathartic, and unruly; the kind of thing that- to bluntly borrow from the lexicon of the very industry being skewered- cannot be neatly plated. Therefor the perverse industrial complex of the perennial high-end restaurant is thusly uniquely ill equipped to communicate what food means to us. With this conceit in mind, beyond a genuinely emotional journey, Pig justifies its existence and thesis to a marvellously acute degree. Yes this is the movie with Nicholas Cage and his pig.

You read any brief description, review, whatever, about Pig, directed by Michael Sarnoski, and they all include some variant of the line, “not just John Wick but with a pig”. Such a qualification has a pretty reductive sentiment behind it (not that the John Wick movies aren’t fucking awesome), as the trailers don’t really imply such a violent journey. That being said, the aesthetic of a bloody and bruised Nicholas Cage looking like he got mauled by a bear and is just as angry as you’d expect about it certainly implies the mood of a deranged man on the edge and ready to snap at any time. This tension is embedded into many of Pig’s scenes and serves as an effective bit of visual misdirection. This film is at times violent but rarely in the ways you’d expect.

What Pig is about is a man and his pig… right. Nicholas Cage plays Robin Feld, a retired chef of somewhat legendary, indeed near mythic, status in the bleeding edge Portland food scene. Long since abandoning his restaurant empire after the death of his wife (ok fine it has some John Wick similarities so sue me), Feld has retreated into the rural Oregon outskirts to lead a seemingly libertarian life off the grid with no company other than his admittedly very cute pig. The pig helps him hunt for truffles in the picturesque hinterlands of the Pacific Northwest, which he then sells to restaurant suppliers. His principal buyer is an up and coming purveyor of gourmet ingredients in the Portland food scene, the ambitious if conceited Amir, played by Alex Wolff, who at least isn’t having as bad a time as he did in Hereditary. Feld’s relationship with Amir is defined by no questions asked vagaries as much as business like reciprocity. They aren’t friends, and Amir doesn’t truly know who Feld is. But Feld doesn’t really have any friends. When he is violently attacked and his pig is brutally stolen from him by mysterious assailants, Amir is really the only person Feld can go to for help; the only person he knows at all.

Across Pig’s three acts Feld and Amir, who is at first reluctantly along for the ride, dig deeper and deeper into the seedy and morally onerous underworld of Portland’s food scene in search for the missing pig. The clarity of Portland’s urban beauty, a mixture of ruggedly authenticity and architectural precision as symbolized by its many bridges, slowly diffuses into a claustrophobic array of labyrinthine visual obfuscation. The film in this regard does an excellent job of priming you for a decent into the unknown. Indeed the developing intrigue of what goes on behind the scenes is rather captivating, shedding a light on the literal underground of Portland’s secret past through the lens of the underbelly of its legacy and trendy restaurants. Sadomasochistic fight clubs, hired goons, facsimiles of mafia dons, and more malignant forms of subtle control all make up the burrowing tendrils and firmaments that prop up the glamour of food culture. This is obviously a fiction, but for those of us that have worked in the industry, it plays into sentiments and cynical ponderances that we have all had about what goes on at the top and where the top meets the bottom. At the very least it justifies the occasional hatred he have against some of our suppliers.

While the hypotheticals of a salacious restaurant underworld as rendered through the lens of someone like Fincher certainly makes for engaging moments- the manner in which Cage has to earn information about the whereabouts of his pig is particularly rough- it’s the pearlescent surface that is shown to the rest of the world that takes the brunt of Pig’s invective; rightly so. In a slyly sub textual aside to the unrelenting restaurant obsession with deconstructing ingredients and palates, so to does the narrative dismantle the artifice behind all of it. This is an industry, whose malevolent but ostensible true colours are personified by an odious middle venue operator, well aware of Feld’s storied history, that says to him, “You don’t have any value, you don’t exist anymore”. A person’s worth in this industry is affixed only to the trends they can claim adjacency to; the positive reviews or word of mouth they can garner. Without those things, they are nothing; this is the culture. Elsewhere in the film when Feld and Amir are covertly on a mission to uncover more pig related clues they dine at one of the currently trendy lunch spots in Portland. While Feld remains stoic and taciturn, one can’t help but sense the eye roll he is keeping at bay as the server gives them an almost aggressively pretentious spiel as to the integrity of not just the ingredients or the method, but the atmosphere of the meal they are going to have. Feld wants not of it, literally sticking his thumb in the food in a wonderfully blunt metaphor. The film ably and eloquently uses Feld’s jaded and weathered persona as an explicit contrast to the pristine and nearly hedonistic privilege behind foodie elitism. Cage’s bloodied and fed up façade juxtaposed by act titles that you’d see on a Hawksworth menu encapsulates the dichotomy perfectly. One wonders what is going on his head at the time.

The film does not mince ideas about the moral vacuum such cultural elitism takes place in, and how it coalesces into straight up evil without much of a narrative or, crucially, rhetorical leap. As we dive deeper into the film and the architect of Feld’s misery is revealed, we see the logical end point of such elitism. The vernacular behind trendy restaurant culture transforms so easily into casual villainy as if to confirm the ethical depravity behind such finessed consumerism. At the end of a trail of compromised bussers, cooks, chefs, and influencers is a person who sees this as nothing more than commerce. Those at the top proudly display not just their cultural aristocracy, but also their avarice- how they have weaponized and manipulated the passions and dreams of some into nothing beyond raw transactional calculations.

This of course is true for any industry where art- and food is art- is involved. But having spent all of my adult life in this industry, acutely aware of the razor thin profit margins, the devastation to mental health that so many in the field have been afflicted with, and the funnelling of money away from those that care the most, I find this film intensely satisfying in how it not only understands my sentiments but allows them to metastasize into a sincere and compelling story. I don’t mind saying that I grew pretty disillusioned by the pretension that permeates the restaurant industry, to the point where I wonder if I want to ever go back. I also recognize that I simply may just not have the appetite for it in the way that a lot of other people I worked with- many of whom are amazing and deserve all the success they have worked for- do. I’m glad Pig takes the time to see it from this perspective.

If that’s as far as Pig took it- as far as my own internalized opprobrium- that would be fine I suppose. But the film takes things several steps further than I was ever willing to do. Pig does appreciate food- absolutely it does. Rather than simply lambasting the culture of food, it looks for the merit more deeply and intrinsically at its core. It saves this for later in the film, actively trying to dissociate from that pretension and instead connect it with ideas of community and healing. Going back to that act two restaurant scene, Cage’s tone switches from derisive apathy as the Chef, a former prep cook of his, drones on and on about his restaurant concept, to actually searching for a way to connect with him. Feld recalls how the once incompetent cook- now a prestigious chef- formerly wanted to open a simple pub. As the conversation segues from discomforting to oddly cathartic you see how much Feld remembered about him, how much he valued his old employee’s dreams, earnestly urging him to reconnect with those dreams and not be beholden to critics and the pretentious intelligentsia that eats his food. “You live your life for them, and they don’t even see you”, he pleads as both of them breathe heavier, reconnecting with memories that they would rather have expunged. He concludes, “We don’t get a lot of things to really care about”. That’s honestly one of the best delivered lines I’ve seen in a movie in a long time.

Later on in the film Feld has another discussion about food with a baker. All of the glamorous trappings of a high end restaurant are supplanted for a humble café. The lyrical gymnastics that go into describing a dish are discarded for genuine admiration behind the skill of it. Here Feld is engaged. When offered a parting gift in the form of a baked good he humbly asks for a second. Not because they look that good (the look pretty good though!), but because he wants to get one for Amir, who Feld is starting to consider might actually be his friend. After all, they’ve shared several meals together at this point.

That sense of disarming empathy culminates in the film’s climax. As tensions rise and desperation sets in one can be forgiven for thinking that Feld truly will snap, especially with the film’s antagonist glibly revelling in his own malice and assured immunization from consequences. Instead the film brilliantly weaves the tangential back story of Amir’s family with the idea of how sensations like taste and smell can elicit, but also define, emotions and memory. To say a bonding experience happens is not exactly accurate; indeed things get quite traumatic in the end. But when Feld says he remembers every meal he’s ever cooked, every guest he’s ever talked to, you know he’s telling the truth. That the particular memories being evoked through Feld’s cooking in the end clarify for the characters on screen at the exact same time as the viewer- in other words, when you figure out what his seemingly esoteric plan was- is a remarkable achievement in minimalist story telling. No one in the room is immune to the ramifications and impact of one specific dish, made with one specific intent. It’s this moment that you’ll look back on and think how wild it ever was to suggest this film was a John Wick clone.

In the second act of the film one of the characters intones, “There’s really nothing here for most of us”. That’s a sentiment that so many of us in the restaurant industry have likely had as the pandemic chewed a lot of us up and spit us out. But by the end of Pig, the film invites you not so much to reconsider that sentiment but to consider the different ways food can mean things to other people, not to ourselves. Even if it doesn’t mean much to you personally (it really doesn’t to me but here I am writing about it), it earnestly and profoundly asks us to understand why it might to other people. All of the characters get there in their own way by the film’s end, and yet all end up in different points along the spectrum of personal growth. It’s messy, in other words. And it’s draining, debilitating even. But I’d wager so are some of the best meals any of us have ever had. You can probably remember some of them. -Tristan

Myanmar Has Fallen

via BBC

Just remember this, when you think you have it bad, someone most certainly has it worse. It’s really easy to cry and whine about all the ills your life has at any given moment, but in reality, with a wider outlook on the state of things within your world, for most of us, life isn’t all that bad. I say this with as much brevity and context one can muster. I realize everyone’s life is different and that grouping any particular individual into a status of doing great versus doing poorly isn’t ideal. I know this. However, in spite of this realization, have a look at the people of Myanmar and let me know how you’d handle your reality.

From The New York Times:

They Wait Hours to Withdraw Cash, but Most A.T.M.s Are Empty

Myanmar has been crippled by a cash shortage since the military seized power six months ago, plunging the Southeast Asian nation into a financial crisis.

The customers, desperate for cash, began lining up at the A.T.M. at 3:30 a.m. By dawn, the queue had swelled to more than 300 people. By noon, when temperatures had reached 100 degrees, many were still waiting, hoping this would be the day they could finally withdraw money from their own bank accounts.

Since the military seized power in a coup six months ago, Myanmar has been crippled by a cash shortage. To help prevent a run on the banks, randomly selected A.T.M.s are stocked with cash daily, and withdrawals are capped at the equivalent of $120.

The economic fallout has had sweeping consequences. With cash in short supply, depositors can’t withdraw their savings, customers can’t pay businesses and businesses can’t pay their workers or creditors. Loans and debts go uncollected. The value of the kyat, Myanmar’s currency, has tumbled 20 percent against the dollar.

Fewer than 100 A.T.M.s now have cash each day across the Southeast Asian nation. Currency hoarding has become widespread and many businesses will accept only cash, not digital bank transfers.

There’s difficulty all over the world. The pandemic has exacerbated numerous issues for everyone, big or small. Economies struggle. People are dying. Work or water is drying up. Fires rage. The world, to put things bluntly, is a mess. So when I came across this story, I was perplexed by its narrative. Why is this happening? What does the government have to gain in acting this way?

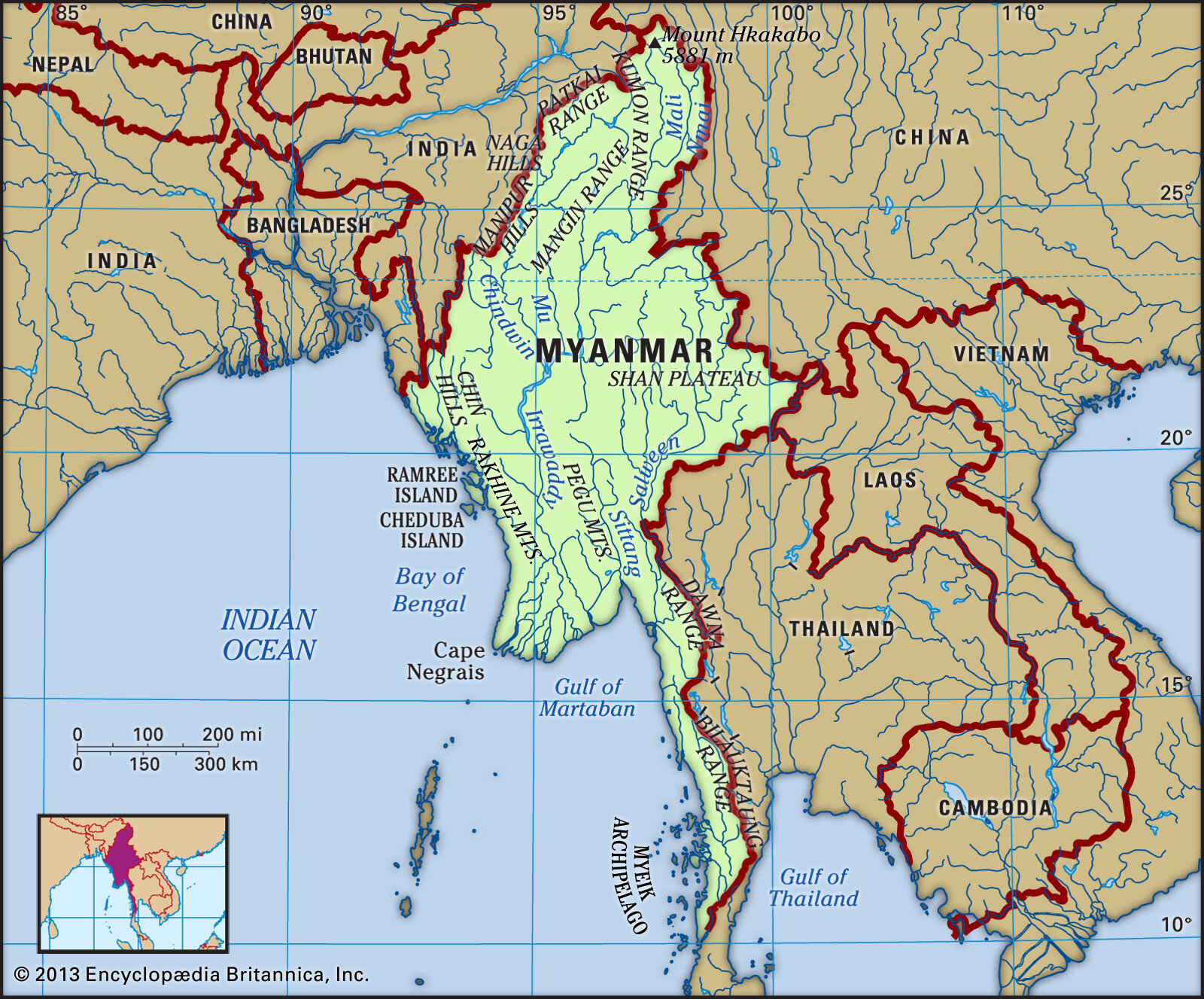

I have a sneaking suspicion a lot of you have no idea where Myanmar is. Here’s a map for you. It’s next to Thailand.

The Skinny:

From the BBC:

Myanmar, also known as Burma, is in South East Asia. It neighbours Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, China and India.

It has a population of about 54 million, most of whom are Burmese speakers, although other languages are also spoken. The biggest city is Yangon (Rangoon), but the capital is Nay Pyi Taw.

The main religion is Buddhism. There are many ethnic groups in the country, including Rohingya Muslims.

The country gained independence from Britain in 1948. It was ruled by the armed forces from 1962 until 2011, when a new government began ushering in a return to civilian rule.

A lot of people were worried Donald Trump would have used the US military to stage a coup after his unsuccessful re-election bid. Thankfully it never materialized, but I’m sure he considered it. Democracy isn’t a given in any society, it must be upheld and bolstered by its citizenry to stay alive. Fascism exists in the US in some form. The January 6th raid on the Capital was a stark reminder of how close that country came from losing itself. We may think we are different here in Canada, but we aren’t that far off. We can lay prey to dictatorship at any time in the wrong hands. Do not take for granted the spoils which we greatly receive. Most aren’t so lucky.

What the hell is going on?

The military in Myanmar took over the country after a fair election won by Ms Suu Kyi’s NLD party. They have placed Myanmar under a one year state of emergency. Hence the run on cash.

From the BBC:

The armed forces had backed the opposition, who were demanding a rerun of the vote, claiming widespread fraud.

The election commission said there was no evidence to support these claims.

The coup took place as a new session of parliament was set to open.

Ms Suu Kyi has been held at an unknown location since the coup. She is facing various charges, including violating the country’s official secrets act, possessing illegal walkie-talkies and publishing information that may “cause fear or alarm”.

NLD MPs who managed to escape arrest formed a new group in hiding. Their leader has urged protesters to defend themselves against the crackdown.

Does part of this sound strikingly similar to what did and could have happened back in the US in January? I feel for the citizens of Myanmar. Forced to wait in lines daily just to pay their bills and eat. Power corrupts and it’s just a shame so many have to endure hardship because a select few care so little.

I had a friend ask me recently why I choose to read as much as I do. He wondered what was the point? (Let that one sink in. How often do you hear that?)

Nevertheless, for him, he just didn’t see the point to learning about life and the world when so little of it is beyond my reality. In a way, I can see his point. But for the most part, I feel he is completely wrong on this issue. Understanding the world around you helps one to grasp the vagaries of what others do and live by. It gives one empathy and compassion and hopefully grace. Knowledge is power and with it comes awareness.

Myanmar is a country far away from my own. I might never visit there. But their current reality is one we should know of. We are all connected as humans and we should want the best for those whom we do not know.

Why?

Because you never know when the tables could be turned on us. - Jamie

The Customer Is Not Always Right

In mid March of 2020 the pandemic hit. Life stopped on a dime and the world fell silent. We had no idea what hit us. Whether you were a full believer or not, your life was altered in some way. Fast forward 15 months and society for the most part in the western world has returned to a bit of normalcy. Borders are opening and people are congregating. With this new wave of freedom, eagerness has ensued.

Starved for so many things, people are back to partake in all the spoils they have missed. As someone who works in the hospitality sector, coming back to work has brought with it new challenges. Policing patrons has become a routine annoyance. Most abide, some do not. This is to be expected. But should it be? And have things gotten worse?

From The Atlantic:

AMERICAN SHOPPERS ARE A NIGHTMARE

Customers were this awful long before the pandemic.

In may, I stood in the rear galley of an airplane and watched as a line formed to berate the flight attendant next to me. We were at a gate at LaGuardia, our flight half an hour delayed, and the air inside the cabin was acrid with the aromas of anxiety sweat and bags of fast food procured at the gate. Impatient passengers squeezed past others hoisting carry-ons into overhead bins to jockey for position in the complaining queue, lodging grievances largely about things over which a flight attendant would have obviously little control: the airline’s decision to sell middle seats, the disruptive wait, the insolent tone of a different flight attendant.

I was tucked inside one of the tiny spaces usually reserved for the flight crew, because I had arrived at my assigned seat to find a man who had no intention of getting up. He gave nothing in the way of an explanation; instead, he stared up at me blankly, as though he had never before encountered the concept of assigned seating. The flight attendant had noticed our stalemate and offered to roust the man from my seat, but the situation felt too combustible to me, and 25C like too stupid a hill on which to die. The attendant said he’d find me another if I’d just wait in the back.

Since I’d arrived at the airport, I had been silently debating whether the conditions of the already dismal experience of flying had deteriorated even further since I’d last boarded a plane, in early 2020. I couldn’t put my finger on any concrete changes beyond the need to wear a mask — a minor, reasonable annoyance. It seemed worse, but after 15 months on the ground, maybe I just remembered flying as slightly better than it had been. When the last of the angry customers had been placated, I asked the flight attendant the question I’d been trying to answer all day.

He didn’t hesitate. “Yeah,” he told me. “It’s way worse.”

This essay by Atlantic staff writer Amanda Mull is fantastic on so many levels as it hits on an issue I’ve been hearing ad nauseam of late. Customers are rude and unruly and it’s way worse than before.

Two years ago I wrote a column detailing the struggles the hospitality industry deals with in regards to its status amongst other professions. At the time I declared the topic a third class problem. It still is to some degree, especially with the exodus of workers the sector has had to reckon with since reopening. People don’t leave their jobs if they are top rate. Hospitality still has an image problem. This is an even bigger topic I’ll leave for another day.

In the meantime, even in light of the field I work within, Mull’s essay touches on a larger problem at play here, one of power and servitude.

For generations, American shoppers have been trained to be nightmares. The pandemic has shown just how desperately the consumer class clings to the feeling of being served.

If you have limited or zero control on most of the things in your life, it stands to reason that you will seek out any opportunity to flip the script so to speak when given the chance. When a greater percentage of a countries workforce serves things versus makes things, this dynamic of power will flourish between the those who consume and those who deliver.

Because consumer identities are constructed by external forces, Strasser said, they are uniquely vulnerable, and the people who hold them are uniquely insecure. If your self-perception is predicated on how you spend your money, then you have to keep spending it, especially if your overall class status has become precarious, as it has for millions of middle-class people in the past few decades. At some point, one of those transactions will be acutely unsatisfying. Those instances, instead of being minor and routine inconveniences, destabilize something inside people, Strasser told me. Although Americans at pretty much every income level have now been socialized into this behavior by the pervasiveness of consumer life, its breakdown can be a reminder of the psychological trap of middle-classness, the one that service-worker deference to consumers allows people to forget temporarily: You know, deep down, that you’re not as rich or as powerful as you’ve been made to feel by the people who want something from you. Your station in life is much more similar to that of the cashier or the receptionist than to the person who signs their paychecks.

A vast majority of people are not happy in their day-to-day lives. They are either too afraid to make change or they’re content just enough to stand idle. Nonetheless, this friction and anxiety manifests at some point. We’re beginning to learn who the scapegoats are. I’m not sure how this can be fixed. — Jamie

Things From The Internet We Liked

Here’s A Cool Explainer About CGI Skin

Visual effects have pretty much perfected things like explosions and stuff in space, so why is something as anodyne as skin seemingly always out of reach when it comes to perfect fidelity? This Vox explainer dives into what makes it so darn complicated and challenging. Really cool that they reference the 2001 Final Fantasy film; while it may have been a bit of narrative mess, at the time oh wow was that ever cutting edge animation. Not so much anymore!

Bill Maher Comes Thru Once Again With A New Rule

This is amazing.

It’s 2021 And You’re Getting A Nas X Lauryn Hill Song

As Kanye does what ever the hell he’s doing with Donda for as long as people will pay attention, Nas just quietly went up and released a new album, King’s Disease II. While a lot of it harkens back to the nostalgia of the 90s when Illmatic was blowing our minds, that sentiment manifests a bit literally when he teams up with Lauryn Hill for the dope as hell track Nobody. Mickey and Tristan were debating which of the two have the better verse, which is honestly a pretty good fight to have. Check it out.