Midrange Weekly Oct 11

Your Weekly Round Up On What’s Got The Midrange Staff’s Attention

Midrange Staff @midrangeyvr

Welcome back to Midrange Weekly and happy Thanksgiving to all of our Canadian friends and readers. While the Canadian variant of the holiday sadly lacks the murderously competitive holiday shopping and economic death race between retailers that the American counterpart does, you can usually bet on a getting a pretty decent meal out of it. It’s also a great time to flex those litigious and argumentative muscles with family members to prepare for the figurative (hopefully) Battle Royale that is the upcoming holiday season. If this opening seems oddly laced with combative and fatalistic language, it’s because- you guessed it- Tristan has been watching Squid Game. Ed note: how many times do I have to ask for Tristan to not be allowed to write the intros any more?? Anyways, let’s get it on.

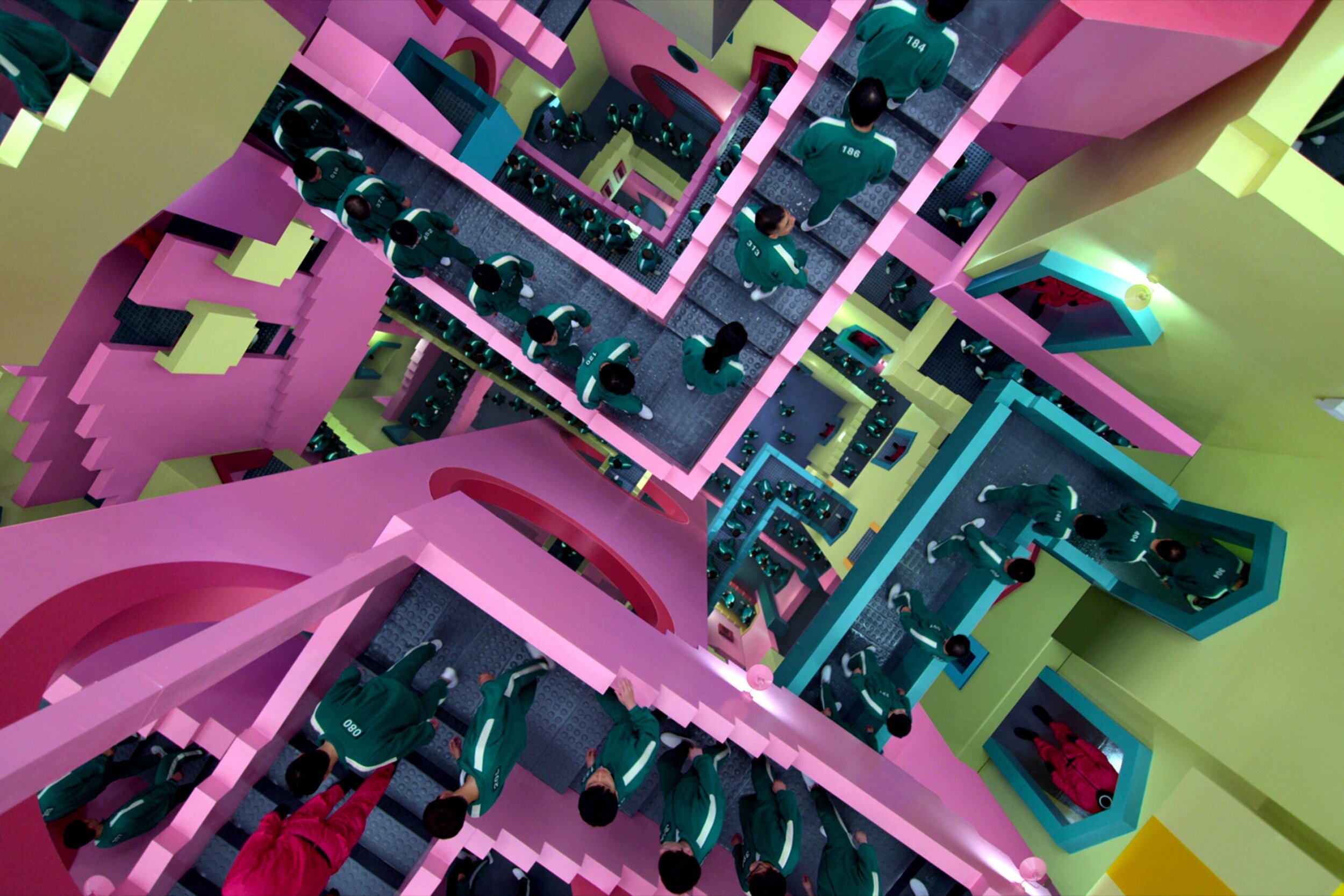

Let’s Talk About Squid Game (Hell Ya)

The most important episode of Squid Game is probably episode two, which ironically is the one people tell me they enjoyed the least. It also takes place almost completely outside of the titular games and is therefore considered the most dissociated from the show’s bonkers and alluring premise. No one dies in episode two, nor is there a twisted or dystopian recreation of a kids game that replaces whimsical nostalgia with a melancholic sense of inevitable doom. It just shows all of the main characters trying to live their lives as best they can. But it is inexorably the scariest episode of them all, as it is the one that justifies the premise of the show and the exploitive games it is oriented around. What is presented initially as absurdist horror fantasy and surreal fatalism in the forms of enigmatic games that promise a life changing amount of money upon victory becomes a logical and even preferable option when faced with the other, which is of course simply being forced to live your life as it is. When a Battle Royal comprised of garish color pallets and uncompromising brutalism seems like a better choice than life in the real world, it reveals the extent of how hostile and inhospitable our world has become. Squid Game is not a critique on the modern age, it is the modern age, reflected and refracted through a fun house mirror that starts to look more and more like the original composite by the end.

Squid Game, laboriously created over a 10 year period by Hwang Dong-hyuk, is the logical extension, but probably not conclusion- of the Battle Royale sub genre that swept Asian cinema and cultural appetites over 20 years ago. It explores the lives of Korea’s poorest and most destitute as their desperation backs them into accepting invitations to a mysterious games to which they know very little of. They lack any explanation on what the games will be or the granular details of the rules until right before they have to play. The shifting dynamics of partnership, teamwork, and opponents sow uncertainty and distrust between the hundreds of players that have signed up. There is certainly no forewarning that should you be eliminated from a game means you are in fact violently murdered right then and there. This revelatory moment in episode one carries a certain amount of enormity in the palpable and communal trauma wrought upon the contestants as they discover the grim reality of these games the hard way. The legalese behind their voluntary admittance into the games provides them a loophole to quit, of which the majority of the contestants take. Freed from the murderous grips of these games, our characters return to their real lives, once again trapped in their varying sub optimal circumstances. Then they decide to go back to the games. They go back.

If that’s not a condemnation of a society so obsessively oriented around the disequilibrium of capitalism, I don’t know what is. Squid Game is a microcosm of what the cynical pursuit of wealth does to us, but it’s worth exploring the broader context of Korean socio-economics that situates all of this into something unenviably plausible. If you’ve noticed something of a predilection in Korean drama towards class divides, horrifyingly extreme poverty, and a near dystopian lack of social or economic mobility it’s because such notions are not just endemic of Korean culture, they are definitive. South Korea, a nation with an impressively robust economic out put and GDP, also has an obscenely high suicide rate and precipitously low birth rate. As the manufacturing sector of Korea shifted more into commerce and economic services, with labour unions being squeezed out, an entire middle class of Korean works were unceremoniously down graded far below the poverty line, with little recourse or options to reverse these trends. The socio economic anxiety we all face to one degree or another in the west is far more acute in Korea, which makes something like Squid Game possible, albeit only in fiction.

We can see these anxieties manifest subtly in the character Sae-byeok, a young North Korean refugee, who’s only real goal in life is to look out for her younger brother and smuggle her mother across the DMZ boarder. Not even 20 and with her whole life ahead of her, Sae-byeok is nevertheless resigned to the cynical calculation that she has nothing really to live or hope for, nothing ahead of her other than the inevitability of death. That nihilist fatalism permeates her character, via her nuanced hostility and fearful introversion. With circumstances such as hers a series of twisted games to the death that at least hold the possibility of a cash prize at the end doesn’t seem objectively worse than her own reality. These crude assessments of reducing life down to dying poor or dying for a chance to get rich are distilled through all of the characters that partake. All of them are riddled with astronomical debts that they have no hopes of paying off. Our characters, all of differing and malleable moral fibres are facing indictments, felonious loan sharks, exorbitant medical bills, and murderous gangsters. Main character, the endlessly affable Seong Gi-hun lives off the dime of his almost as poor mother, has an ex wife that hates him, a daughter being excised from his life, an insatiable gambling addiction and the attendant loan sharks to go with it. He has no options, no means of rectifying any of these singularly devastating tenants of his life. Keep this in mind and consider the 1981 film The Running Man, in which our revolutionary hero is forced against his will to compete in similarly murderous (although more athletically oriented) games. In Squid Game they are choosing to kill each other for money, willingly.

They aren’t bad people- well most of them. Rather victims of the exigencies of late stage market capitalism. Even the ostensibly good people will at one point or another be driven to murder, or at least the cynical tactical instincts that put self preservation above the well beings of others. What’s distinctive and troublingly sincere about Squid Game is that of the myriad times we have seen this before in fiction, it’s never in something as nominally low stakes as children’s games. The show explores not just the effects of dehumanization but the vectors it can, apparently very easily develop upon. How far can it go, how easily can it get so far? The answers the show posits are frightening, depicted with an urgency of a loaded gun ready to go off at any time should the rules of simple games not be followed. Life or death situations juxtaposed through leisurely activities for youth serves as a metaphor for just how little it takes to reduce us to our baser and brutal instincts, but the show also assiduously points out that this only works on people living on the precipice of oblivion in perpetuity. The games pushed them over the edge of moral depravity sure, but it was the real world that wore them down and primed them for such an ethical leap. The toxic effects of capitalism act as something of a pernicious force multiplier in this regard.

That toxin is more malignant than one would first assume, but its true deleterious potency becomes more apparent as we watch the old man character Il-nam wax nostalgically about playing these games in his youth. The genuine euphoria that comes from recalling fond memories is worn so gingerly on the face of him and Gi-hun when they talk about playing these games in the earlier episodes. By the end, mention of the games subsumes them within alternating currents of dread or vicious determination. Squid Game takes the innocent memories of children games and re-contextualizes them, inverting the jubilant recollections into something traumatic, thusly annexing the innocent part of our psyche, leaving only tactical calculation, raw savagery and self preservation as associated tenants of these games. The idea of desperation being translated and transposed into a game to be observed for fun, gambled upon for diversionary sport, observed via an inverse ratio of living contestants or growing prize money (denoting more and more death) becomes a quantifiable symptom of the frivolities of hyper and dead end capitalism.

What’s interesting is this proverbial dead end reveals itself even to those on the top of the economic food chain. The frankly disgusting revelation of the games’ benefactors organizing such a thing to gamble upon the lives of people certain to die at one point or another, relates to a late in the series speech about how wealth and poverty seem to suck the joy out of living in equal measure. This sounds rich (forgive the pun) coming from those that have money, but there is kernel of truth there in that an over reliance, by necessity or frivolity, on economic status anathematizes us to the rest of what life is supposed to offer. This is something we were still cognizant off in our youth, playing our silly games, but are now deprived of such an understanding. Thusly, the whole point of the games becomes less of a social exercise in mapping the extent a person can be driven to do horrible things, and more an elaborate expression of wish fulfilment on a scale commensurate with the wealth of the person that orchestrated it. The fact that even betting and gambling on the outcomes however brought him little joy, only stealthily competing himself as a sleeper agent reconnected him with the youthful happiness long since dissolved away by his wealth, shows just how incongruous the pursuit of wealth is with any kind of real joy. By mustering all the resources and power he had to bring him happiness, he actually articulates the futility in such things. Gi-hun recognized this paradox, which is why he wanted nothing to do with his prize money. Perhaps there is a worse thing than the veritable hell of his every day life in the real world.

Part way through episode five, the ostensible villain of the show, the enigmatic masked man that over sees the squid games lectures one of his goons who was feeding certain contestants information about the game to give them an advantage. The masked man extols, “everyone is equal when they play this game. Here, the players get to play a fair game under the same conditions. These people suffered from inequality and discrimination out in the world. And we’re giving them a last chance to fight fair and win”. Like the same perverse idea that ran through the mind of the contestants when they decided to go back, from a certain perspective the games don’t seem so bad to me. I’ve been thinking about that line a lot. -Tristan

The World Is Coming To Its Senses — Taxation

Google headquarters in Dublin

Two big stories dropped this past week in regards to taxation. The first was the Pandora Papers, a massive document leak exposing the secret offshore accounts of celebrities and politicians.

From CBC:

The offshore fortunes of prime ministers, royalty, billionaires, athletes and celebrities are being laid bare in a giant new leak of tax-haven financial records, even bigger than the Panama Papers, revealed today by a global consortium of media outlets.

The leaked files, dubbed the Pandora Papers, show 35 current or former world leaders and more than 300 other public officials around the globe who have held assets in or through tax havens. Former British prime minister Tony Blair, the current prime ministers of the Czech Republic and Kenya, and the king of Jordan have all benefited from the anonymity or tax advantages of their offshore holdings, the records reveal.

Similar in scope to the Panama Papers leak of 2016, the size of this leak is not only troubling but disheartening. But ultimately, is there any shock to this revelation? None whatsoever.

Moving on.

On Friday, the second big story of this narrative dropped, one which might help curtail this type of chicanery. I say might, because at the end of the day, rich people will go to whatever length they have to in order to keep their money. It’s understandable. Not right, but understandable. Regardless, here’s the skinny.

From The New York Times:

The world’s most powerful nations agreed on Friday to a sweeping overhaul of international tax rules, with officials backing a 15 percent global minimum tax and other changes aimed at cracking down on tax havens that have drained countries of much-needed revenue.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which has been leading the negotiations, said the new minimum tax rate would apply to companies with annual revenue of more than 750 million euros ($866 million) and would generate around $150 billion in additional global tax revenue per year.

“Today’s agreement will make our international tax arrangements fairer and work better,” Mathias Cormann, the organization’s secretary general, said in a statement. “We must now work swiftly and diligently to ensure the effective implementation of this major reform.”

The agreement is the culmination of years of fraught negotiations that were revived this year after President Biden took office and renewed the United States’ commitment to multilateralism. Finance ministers have been racing to finalize the agreement, which they hope will reverse a decades-long race to the bottom of corporate tax rates that have encouraged companies to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions, depriving nations of money they need to build new infrastructure and combat global health crises.

This news is fantastic to hear. Whether it will actually pass and become an agreement remains to be seen. The fact that it will only apply to companies who make more than $866 million seems counterintuitive as it should apply to everyone, but starting somewhere has to happen. This is definitely meant for the Amazon’s of the world. The big fish.

One of the smartest ideas to emerge from this news is the Biden administration led push to have this rule apply to where companies sell their goods and not just where their head office is set up. Again, this is solely meant for the Amazon’s of the world. This is incredibly smart. It prevents avoidance all together.

Ironically, for this news to come out the same week as the Pandora Papers says a lot on where people’s minds are at. Inequality has widened significantly since the beginning of the pandemic. Elon Musk’s wealth has doubled in that span. No one human should be worth $200 billion dollars. No one company should be worth a trillion and pay zero in taxes. Fixing this issue shouldn’t be hard to sway people, but, politics and corruption tend to rear their heads when it comes to the rich and their wealth. Nevertheless, a global tax floor is a good start. - Jamie

Things From The Internet We Liked

The Internet Reacts To Facebook Going Down

Earlier in the week, our fragile world found a brief bit of peace and respite in the form of Facebook/Instagram/WhatsApp going down. Such an outage says a lot about the prodigious effects of tech giant consolidation and monopoly, and this really was a big deal for parts of the world that rely predominantly on WhatsApp for communication. But also, it was so so fun not having to deal with the all that shit for an afternoon. Below are some of the best reactions to the outage when it was happening, all of them from Twitter for err, obvious reasons.

It's almost like hypercentralization of Internet infrastructure is a bad idea

— Evan Greer (@evan_greer) October 4, 2021

omg keep facebook and insta down i’m begging you pic.twitter.com/ymfIZlYgFI

— fROYday the 13th🌾 (@Roy_oh_Roy) October 4, 2021

— Jeppe Locht (@JeppeLocht) October 4, 2021

"You know who else briefly went offline?"

— Robert Downen (@RobDownenChron) October 4, 2021

-Youth pastor

if Facebook is down how many hours realistically do you think I have to radicalize my mom

— Kelly Bachman (@bellykachman) October 4, 2021

hey guys. um so say i hypothetically worked at a big tech company and hypothetically spilled some diet ginger ale on the big um servers in the back room and now a lot of stuff is going wrong. what should i hypothetically do

— kristofer thomas (@kristoferthomas) October 4, 2021

facebook taking the kids (instagram and whatsapp) and leaving before it gets left is a power move you gotta respect

— blaire erskine (@blaireerskine) October 4, 2021

whatever happened at IG and FB, let's just.... not fix it

— jg (@jacquesgreene) October 4, 2021

Instagram and Facebook users checking out Twitter while they’re down pic.twitter.com/MGZoRYmRXl

— James Felton (@JimMFelton) October 4, 2021

Statement from Facebook pic.twitter.com/uCCZbPnyHW

— blaire erskine (@blaireerskine) October 4, 2021

hello literally everyone

— Twitter (@Twitter) October 4, 2021